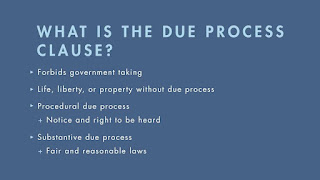

The Fifth Amendment and the Fourth of the Constitution of the United States each contain a legal process clause . The appropriate process relates to the administration of the judiciary and therefore the legal process clause acts as protection from the arbitrary denial of life, liberty or property by the government outside of legal sanctions. The United States Supreme Court interpreted clauses more broadly, concluding that these clauses provide four protections: procedural procedural processes (in civil and criminal proceedings), substantive legal processes, prohibitions on unclear laws, and as vehicles for merger Bill of Rights.

Video Due Process Clause

​​â € <â €

Paragraph 39 Magna Carta is provided:

No free person shall be arrested or imprisoned, or disarmed of his or her rights or property, or prohibited or exiled, or removed from his position by other means, nor shall he proceed with coercion against him, or send others to do so, except by a judgment legitimate of equivalent or by state law.

The phrase "due process of law" first appeared in the imposition of Magna Carta's law in 1354 during the reign of Edward III of England, as follows:

No one of his circumstances or condition shall be expelled from the land or houses or not taken (taken to be captured or deprived of liberty by the state), or withdrawn, or put to death, without him being brought to answer by due process of law.

Maps Due Process Clause

Drafting

New York is the only state that asks Congress to add language "due process" to the US Constitution. New York ratified the US Constitution and proposed the following amendments in 1788:

[N] Persons must be imprisoned or slaughtered from their freehold, or alienated or deprived of their rights, Franchise, Life, Freedom or Property but with due process of law.

In response to this proposal from New York, James Madison drafted a legal process clause for Congress. Madison cut several languages ​​and entered the word without , which has not been proposed by New York. Congress later adopted the exact words Madison proposed after Madison explained that the legal process clause would not be enough to protect various other rights:

Although I know whenever the big rights, the trial by the jury, the freedom of the press, or the freedom of conscience, appear in the [Parliament] body, their invasion is opposed by capable supporters, but their Magna Carta does not contain any provision for the right security -those, who respect the most worried Americans.

Text

The Fifth Amendment of the United States Constitution provides:

No one is... deprived of life, liberty, or property, without legal process...

Part One of the Fourteenth Amendment of the United States Constitution provides:

[N] or any State will deprive anyone of soul, liberty, or property, without legal process...

Interpretation

Coverage

The Supreme Court has interpreted the process clauses required in the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments to be identical, as Judge Felix Frankfurter once explained in a concrete opinion:

Assuming that 'legitimate legal process' means one thing in the Fifth Amendment and the other in the Fourteen is too reckless to ask for a complex rejection.

In 1855, the Supreme Court explained that, to ascertain whether a process is a legal process, the first step is to "examine the constitution itself, to see if this process is contrary to one of its provisions". Also in 1855, the US Supreme Court said,

The words, "due to legal process", are undoubtedly meant to convey the same meaning as the words, "by state law", in Magna Carta.

In 1884 the case of Hurtado v. California , the Court said:

Since the legal process in [Fourteenth Amendment] refers to the laws of the state in each country which obtains its authority from the inherent and legally protected state power, it is given within the confines of the fundamental principles of freedom and justice situated at the bottom of all our civil and political institutions, and the greatest security that is within the right of the people to make their own laws, and to change them with pleasure.

The proper process also applies to the creation of taxation districts, since taxation is a property deprivation. The appropriate process usually requires a public hearing before the establishment of a tax district.

"Status"

Because the process applies to Puerto Rico, even though it is not State.

"Person"

The clauses of the legal process apply to natural persons as well as to "legal persons" (ie, personality of the company) as well as individuals, including citizens and non-citizens. The Fifth Amendment Process The changes were first applied to the company in 1893 by the Supreme Court at Noble v. Union River Logging . Noble preceded by Santa Clara County v. Southern Pacific Railroad in 1886. The legal process clause also applies to non-nationals residing in the United States, although the US Supreme Court has recognized that non-nationals may be terminated, detained, and denied by past immigration officials in entry points (eg at ports or airports) without the protection of the Process Clause Because, while technically on US soil, they are not considered to have entered the United States. "Liberty"

The US Supreme Court has interpreted the term "freedom" in a broad legal process clause:

Although the Court has not yet assumed to define "freedom" with high accuracy, the term is not limited to the sheer freedom of body restraint. Legal freedom extends to a variety of behaviors that individuals are free to pursue, and that can not be restricted except for proper governance purposes.

Country actor

The prohibition, in general, of the legal process clause applies only to acts of state actors, and not to private citizens. However, where individuals act together with state officials in prohibited acts, they are said to act under "legal colors" for the purposes of 42 US. Ã, § 1983. While private actors are generally not held by civilian acts, it remains that private citizens may be liable to crimes responsible for federal or minor crimes, if they conspire with the government to take actions that violate the clause of the process law. constitution.

Procedural legal process

Procedural procedural law requires government officials to follow fair procedures before depriving people's lives, liberties, or property. When the government seeks to deprive a person of one of these interests, the legal process should require the government to pay the person, at least, notice, opportunity to be heard, and a decision made by a neutral decision-maker.

This protection extends to all government processes that could result in the deprivation of individuals, whether civil or criminal, from parole to administrative hearings to hearings on government benefits and the right to a full criminal court. The "Some Kind of Hearing" article written by Judge Henry Friendly lists the basic legal rights "which remain highly influential, both content and relative priorities". These rights, which apply equally to the civil proceedings and criminal proceedings, are:

- An unbiased court.

- The proposed action announcement and the reasons set forth for it.

- Opportunities to present the reasons why the proposed action should not be taken.

- Right to present evidence, including the right to summon witnesses.

- Right to know conflicting evidence.

- The right to cross-check a bad witness.

- The decision is based exclusively on the evidence presented.

- Opportunities to be represented by lawyers.

- The requirement that the court prepare evidence of the evidence presented.

- The requirement that the tribunal prepare written findings on the facts and reasons for its decision.

Civil legal event process

Procedural procedural is basically based on the concept of "fundamental justice". For example, in 1934, the United States Supreme Court declared that the process should be violated "if a practice or rule alludes to some principles of justice rooted in the traditions and consciences of our people who will be classified as fundamental". As interpreted by the court, it includes the right of the individual to be adequately informed of allegations or proceedings, an opportunity to be heard in this process, and that the person or panel makes a final decision on an impartial process in this matter beforehand. they.

Simply put, where an individual faces the deprivation of life, liberty, or property, a reasonable legal process mandates that he is entitled to adequate notice, trial, and a neutral judge.

The Supreme Court has formulated a balancing test to determine the accuracy of which procedural procedural requirements should be applied to certain deprivations, for the obvious reason that the mandate of the requirement in the widest manner even for the smallest omission would bring the government machine to a halt. The Court sets the test as follows: "[I] the sponsorship of specific orders of legal proceedings generally requires consideration of three distinct factors: first, personal interests to be influenced by official action, second, the risk of misappropriation of such interests through the procedures used, possible, if any, additional procedural safeguards or substitutions, and, ultimately, the interests of the Government, including the functions involved and the fiscal and administrative burden that additional procedural requirements or substitutions will require.

Procedural procedural law is also an important factor in the development of the law of private jurisdiction, in the sense that it is inherently unfair to the judicial machinery of a state to take possession of a person who has no relationship to it. Therefore, most US constitutional laws are directed at what type of connection to a country sufficient for a state statement on the jurisdiction of non-residents to comply with procedural procedural processes.

The requirement of a neutral judge has introduced a constitutional dimension to the question of whether the judge should withdraw from a case. In particular, the Supreme Court has ruled that under certain circumstances, the necessary process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment requires the judge to resign because of potential conflicts of interest. For example, in Caperton v. AT Massey Coal Co. (2009), the Court ruled that West Virginia Court of Appeals Court of Appeals could not participate in cases involving a large donor to him. election to the court.

Criminal procedural legal process

In criminal cases, much of the protection of this legal process overlaps with the procedural protection afforded by the Eighth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which ensures a reliable procedure that protects innocent people from execution, clear of cruel and unusual punishment.

An example of the right of criminal proceedings is the case of Vitek v. Jones , 445 U.S. 480 (1980). The necessary process clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment require certain procedural safeguards for inadvertent state detention to a state mental institution for the treatment of mental illness or disability, such protection including written notice of transfer, counter-trial before independent decision-maker, findings written, and effective and timely notice of these rights. As established by the district court and enforced by the US Supreme Court at Vitek v. Jones , these legal process rights include:

- Written notices to inmates that transfer to a psychiatric hospital is under consideration;

- An examination, sufficient after notice to allow prisoners to prepare, where disclosure to inmates is made of reliable evidence for transfer and where the opportunity to be heard personally and to present documentary evidence is provided;

- An opportunity at trial to present witness testimony by the defendant and to face and cross-examine witnesses summoned by the state, except on findings, not arbitrarily made, good reason not to allow such a presentation, confrontation or examination cross;

- Independent decision makers;

- Written statement by the factfinder on reliable evidence and reasons for the transfer of inmates;

- The availability of legal counsel, provided by the state, if the prisoners are financially unable to provide his own (But it should be noted that the majority of judges dismiss this right to provide state-equipped advice.); and

- Effective and timely notice of all rights above.

Substantive legal process

In the mid-19th century, the "legal process" was interpreted by the US Supreme Court which meant that "it was not submitted to legislative powers to enforce possible processes." Articles of legal proceedings are restrictions on the legislature as well as on the executive and judicial powers of the government; can not be so interpreted as to leave Congress free to make the process of 'legal process' by the will alone. "

The term "substantive legal process" (SDP) is commonly used in two ways: first to identify a particular case law line, and secondly to indicate a particular attitude to judicial review under the legal process clause. The term "substantive legal process" began to take shape in legal books of the 1930s as a categorical distinction of selected process cases, and in 1950 was mentioned twice in the opinions of the Supreme Court. SDP involves the challenge of a freedom-based justice process that seeks certain outcomes, not only against its procedures and influence; in such cases, the Supreme Court recognizes constitutional "freedoms" which subsequently enact legislation that seeks to limit such "freedoms," which have no legal or limited force. Critics of the SDP decisions usually claim that freedom must be left to a more politically responsible branch of government.

The court has seen the clauses of the legal process, and sometimes other clauses of the Constitution, because it embraces fundamental rights that are "implied in the concept of freedom being commanded". Just what those rights are is not always clear, so is the authority of the Supreme Court to enforce countless rights clearly. Some of them have a long history or "deep root" in American society.

Courts have abandoned most of the Lochner-era approach (c) 1897-1937) when substantive legal proceedings are used to impose minimum wages and labor laws to protect freedom of contract. Since then, the Supreme Court has ruled that many other freedoms that do not appear in the Constitutional text are still protected by the Constitution. If these rights are not protected by the federal court doctrine of substantive processes, they can still be protected in other ways; for example, it is possible that some of these rights may be protected by other provisions of a state or federal constitution, and alternatively they may be protected by the legislature.

Today, the Court focuses on three types of rights under a substantive process because in the Fourteenth Amendment, originating from the United States of America v. Carolene Products Co. , 304 US 144 (1938), footnote 4. All three types of rights are:

- the first eight amendments in the Bill of Rights (e.g., Eighth Amendment); Restrictions

- on the political process (eg, voting rights, associations, and freedom of speech); and

- the rights of "discrete and insular minorities".

Courts usually look first to see if there is a fundamental right, by checking whether that right can be found rooted in American history and tradition. If rights are not fundamental rights, the courts apply a rational, grounded test: if rights violations can be rationally related to legitimate governmental purposes, then the law applies. If the court determines that the rights that are infringed are fundamental rights, it applies strict supervision. This test asks whether there is an interesting state interest fought for by rights violations, and whether the relevant legislation is narrowly adapted to address the interests of the state.

Privacy, which is not explicitly mentioned in the Constitution, is issued at Griswold v. Connecticut (1965), where the Court declared that a contraceptive criminal banning for a married couple violates federal privacy rights that can be applied in a fair manner. The right to contraception is found in so-called "penumbras" Courts, or shadow edges, of certain amendments which may refer to specific privacy rights. The penumbra rationale of Griswold has been discarded; The Supreme Court now uses a legal process clause as the basis for various unspecified privacy rights. Although it has never been a majority view, some argue that the Ninth Amendment (addressing unspecified rights) can be used as a source of fundamental rights that can be exercised judicially, including the general right to privacy, as discussed by Justice Goldberg, i> Griswold .

Cancel for obscurity

Courts generally stipulate that laws are too vague for the average citizen to understand depriving citizens of their rights to legal proceedings. If the average person can not determine who is governed, what behavior is prohibited, or what penalties may be imposed by law, the court may find that the law does not apply. View Coates v. Cincinnati , where the word "disturb" is considered to be lacking due to a fair warning insertion process.

Establishment of Bill of Rights

Establishment is a legal doctrine whereby the Bill of Rights, whether in full or in part, applies to states through the provisions of the Fourth Amendment process. The foundation for establishment is the substantive legal process of substantive rights mentioned elsewhere in the Constitution, and the applicable legal process of procedural rights mentioned elsewhere in the Constitution.

The establishment began in 1897 with a takeover case, followed by Gitlow v. New York (1925), which was the case of the First Amendment, and accelerated in the 1940s and 1950s. Judge Hugo Black famously liked the jot-for-jot incorporation of all Bill of Rights. However, Judge Felix Frankfurter - later joined Judge John M. Harlan - felt that federal courts should only apply parts of the Bill of Rights that are "fundamental to the freedom of command scheme". It was the last resort taken by the Warren Court in the 1960s, though almost all Bill of Rights have now been put into jot-for-jot against the states. The latest incorporation is the 2nd Amendment which makes the individual and fundamental right to "guard and bear arms" fully applicable to America; see McDonald v. City of Chicago, 561 US (2010).

The role of the incorporation doctrine in applying Bill of Rights guarantees to states is as important as the use of legal proceedings to define new fundamental rights not explicitly guaranteed by the text of the Constitution. In either case, the question is whether the right is "fundamental", so, just as not all new "proposed" constitutional rights are given a judicial recognition, not all provisions of the Bill of Rights have been deemed sufficiently fundamental to be justified. law enforcement to the state.

Some people, such as Justice Black, have stated that the Privileged Clause or Immunity of the Fourteenth Amendment will be a more appropriate textual source for the doctrine of incorporation. The court has not taken such a step, and a few points on the treatment granted to the Privilege Claim or Immunity in 1873 The Case of Massacre as the reason why. Although the Court of Cutting Cut does not explicitly block the application of the Bill of Rights to the state, the clause is largely cease to be used in Court opinion after the Cutting House Case, and when establishment begins, it is under the rubric of legal process. Scholars who share views of Justice Black, such as Akhil Amar, argue that Framers of the Fourteenth Amendment, such as Senator Jacob Howard and Congressman John Bingham, include the process clause required in the Fourteenth Amendment for the following reasons: "By incorporating the Fifth Amendment rights , privileges or an immunity clause will... have prevented the state from depriving the citizens of the legal proceedings Bingham, Howard, and the company want to go further by extending the benefits of the legal process of the country to foreigners.

The Supreme Court has consistently maintained that the process of amending the Fifth Amendment is substantially the same as the Fourth Amendment amendment process, and therefore the original meaning of the former is relevant to the doctrine of incorporation from the latter. When the Bill of Rights was originally submitted by Congress in 1789 to the state, various substantive and procedural rights were "classified according to their affinity to each other" rather than submitted to the state "as a measure to adopt or be rejected in the dirty", as James Madison. Roger Sherman explained in 1789 that any amendment "can be clearly forwarded by America, and any adopted by three quarters of the legislature can be part of the Constitution". Accordingly, States are permitted to reject the Sixth Amendment, for example, while ratifying all other amendments including legal process clauses; in this case, the rights in the Sixth Amendment will not be entered against the federal government. The doctrine of incorporating the contents of other amendments into "legal proceedings" is an innovation, when it began in 1925 with the case of Gitlow , and this doctrine is still controversial today.

Merging of same protection

In Bolling v. Sharpe 347 U.S. 497 (1954), the Supreme Court declared that "the concept of equal protection and legal process, both derived from our American ideals of justice, are not mutually exclusive." The Court thus interprets the clause of the Fifth Amendment legal process to include an equivalent element of protection. In Lawrence v. Texas, the Supreme Court added: "Treatment equality and appropriate processes to demand respect for behavior are protected by substantive guarantees of related freedom in important matters, and decisions on the latter, the point of progress of both interests." Inspection rate

When laws or other government actions are challenged as violations of individual freedoms under the clauses of the legal process, the courts currently primarily use two forms of examination, or judicial review, used by the Judicial Branch. This investigation balances the importance of the interests of the government served and the appropriateness of the methods of the government's implementation of violations resulting from the rights of individuals. If government action violates fundamental rights, the highest review level - strict supervision - is used. To pass a rigorous examination, laws or laws must be narrowly adapted for the benefit of a stronger government.

When government restrictions limit freedom in a way that does not imply basic rights, rational basic review is used. Here the legitimate governmental interest is sufficient to pass this review. There is also intermediate level supervision, called intermediate supervision, but is mainly used in the case of Protection of Equations rather than in cases of Process Due.

Remedies

The trial was held in 1967 that "we can not leave the United States to formulate an... authoritative effort designed to protect people from infringement by States guaranteed by federal rights".

Criticism

Substantive legal process

Critics of substantive legal processes often claim that the doctrine began, at the federal level, with the famous 1857 slave case of Dred Scott v. Sandford . However, other critics argue that the process is substantive since it was not used by the federal court until after the Fourteenth Amendment was adopted in 1869. The proponents of the substantive process owing to the claim that the doctrine was used in Dred Scott claim that it was not used correctly. In addition, the first appearance of a legitimate process as a concept could be spelled out earlier in the case of Bloomer v. McQuewan, 55 US 539 (1852), so Supreme Court Justice Taney would not entirely violate in his opinion Dred Scott when he declared Missouri Compromise unconstitutional because, among other reasons, the "action A congress depriving citizenship or property is only because he came by himself or brought his property into a certain territory in the United States, and who does not violate the law, can hardly be dignified by the name of the applicable legal process ". Dissenting Justice Curtis disagrees with Taney about what "due process" is meant in Dred Scott .

Criticism of doctrine continues as in the past. Critics argue that judges make decisions on the policies and morality that legislators ought to have (ie "make rules from the bench"), or argue that the judge reads a view into the Constitution that is not really implied by the document, or argues that the judge claims the power to expand freedom of some people at the expense of others' freedoms (such as in the case of Dred Scott), or argue that judges handle substance, not process.

Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., a realist, is worried that the Court goes beyond its limits, and the following is from one of those who disagree:

I have not adequately expressed more of the anxiety I feel in the increasing scope given to the Fourteenth Amendment in cutting what I believe to be the constitutional right of the State. Because the decision now stands, I see almost no limit but the sky against the cancellation of those rights if they hit most of these Courts for any unintended reason. I do not believe that the Amendment is intended to give us full power to realize our economic or moral belief in its prohibition. But I can not think of a narrower reason for me to justify the present decision and the previous decision I have referred to. Of course the words legal proceedings , if taken in the literal sense, have no application for this case; and although it is too late to deny that they have been given a much broader and artificial meaning, we still have to remember the caution shown by the Constitution in restricting American power, and must be slow to interpret the clause in the Fourteent Amendment as committed to the Court, guidelines, but the Court's own discretion, the legitimacy of any law which may be endorsed by the State.

Originals, such as High Court Judge Clarence Thomas, rejected the doctrine of substantive judicial proceedings, and Chief Justice Antonin Scalia, who also questioned the legitimacy of doctrine, called the substantive process a "judicial plunder" or "oxymoron". Both Scalia and Thomas sometimes join the opinions of the Courts that mention the doctrine, and in their disagreements often argue about how a fundamental judicial process should be employed based on the precedent of the Court.

Many non-original, such as Justice Byron White, are also critical of substantive legal processes. As noted in his dissenting opinion at Moore v. East Cleveland and Roe v. Wade , as well as the majority opinion in Bowers v. Hardwick , White argued that the doctrine of a substantive process gives too much power to the judiciary of government and removes such power from the branches of elected government. He argues that the fact that the Court has created a new substantive right in the past should not lead it to "repeat the process at will". In his book Democracy and Distrust, non-originist John Hart Ely criticized the "substantive legal process" as a striking non-repetition. Ely thought it was a contradictory term, like the green pastel phrase.

Originality is usually associated with opposition to the rights of substantive judicial proceedings, and the reason for it can be found in the following explanation unanimously endorsed by the Supreme Court in a 1985 case: "[W] e must always be kept in mind that the substantive content of the clause [due process] is not recommended either by language or by pre-constitutional history, that content is no more than the product of accumulation of judicial interpretations of the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments. "

Originalists do not always oppose the protection of rights previously protected by using substantive legal processes; on the contrary, most originalists believe that such rights should be identified and protected by law, through amendments to the constitution, or through other provisions of the Constitution.

The perceived coverage of the legal process clause is initially different from now. For example, although many of the Framers of the Bill of Rights believe that slavery violates the natural rights of African-Americans, a "theory that says slavery is a violation of the necessary process clauses of the Fifth Amendment... requires no more than a suspension of reason origin, purpose, and past interpretation of the clause ".

Legal process clause in country constitution

No state or federal constitution in the US has ever used the word "due process" before 1791 when the federal Bill of Rights was ratified.

New York

In New York, the rights law was issued in 1787, and contained four different legal process clauses. Alexander Hamilton commented on the language of New York's rights law: "The words 'legal process' have proper technical imports, and apply only to justice processes and proceedings; they can never be referred to an act of the legislature."

References

Source of the article : Wikipedia